The origin of tetrapods, a summary.

The formation of the vertebrate embryos goes through a series of hydrodynamic, fluid, movements. These occur in quite young "embryos" at a stage where they are not even called embryos (blastula). At that stage, they are round, and we may agree : formless. The embryo itself forms from one part of this blastula. The rest forms the extra-embryonic organs (especially, the avian yolk sac in the case of chicken embryos, which is the equivalent of the human placenta).

By hydrodynamic, it is meant that the very young embryo is a viscous material, which flows, under the action of volume forces which are the cell tractions. The fact that the cells are in tight contact implies that any displacement of any cell, imparts a long range deformation field on the other cells. This is a property of condensed matter, much like if you pull at one end on a material, say a blanket, you may feel a drag at the other end. This interaction is independent of the chemistry, except for the actual values of the parameters, it is solely the writing of the material equilibrium under a traction force. All materials will actually generate such internal stresses, be them elastic or viscous materials. The stress pattern is actually very close in either cases. When a book is put on a shelf, it flexes, in the same way, when a cell pulls on a thin film, there is a dipolar drag. In order to find the global movement imparted by the action of all cells one has to add up (integrate) all the dipoles created by each cell, and to treat the displacement of the said cells into their own movement. This is why a field theory is needed.

The movements I am writing about have been seen for long. But bizarrely enough, their description is erroneous. At least, this is my opinion.

From R. Wetzel, Untersuchungen am Hühnchen. Die Entwicklung

des Keims während der ersten beiden Bruttage, Arch. Entw. Mech. Org.

119, 188 (1929).

(Addendum 2012: actually, this figure is quoted by several authors, but when one reads the original article, one finds a drawing showing

a caudal retrograde flow too. Wetzel draws a set of arrows which suggests a hyperbolic flow in the caudal area.

The other figure can be found here http://www.msc.univ-paris-diderot.fr/~vfleury/portalvortices.html

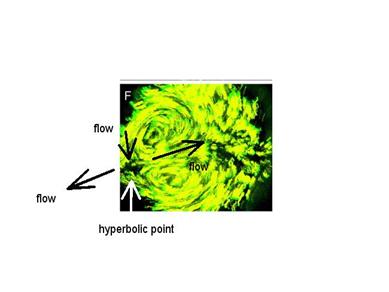

In fact, as described for the first time in (V. Fleury, Organogenesis, 2, 1, 6 2005 et V. Fleury, Revue des Questions Scientifiques, 177, 3-4, 235 (2006)), the flows exhibit a saddle-point, with hyperbolic lines flowing away in the anterior and the posterior direction, away from a point of zero speed (stagnation point).

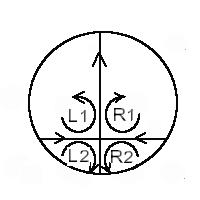

A stagnation point splits the space into four quadrants around which lines wind with opposite windings such that the direction of the flow are opposite (+,-,+,-) (one component of the direction of the flow reverses across lines where the flow is straight here horizontal and vertical directions).

The line vorticities (if zero, say just the windings) are of opposite signs, when going from one quadrant to the next, because of conservation laws around the saddle point (div (V)=0) (the winding is clockwise, then anti-clockwise etc., in the 4 quadrants of the saddle point).

I believe that the very fact that there existed a flow oriented caudally was so difficult to admit or understand that researchers of the past just "did not see it". This tendency is very obvious on present work. In most articles, our colleagues always show the saddle-point somewhat laterally, by the edge of the picture, or even off-sight. For example in :

From : C. Cui, X. Yang, M. Chuai,

J. A. Glazier, C. J. Weijer, Dev.

Biol. 284, 37

(2005). Imaging of cellular paths by fluorescence techniques. I have added the arrows.

and in :

From, Cooperation of polarized cell

intercalations drives convergence and extension of presomitic mesoderm during zebrafish gastrulation, Chunyue

Yin, Maria Kiskowski,

Philippe-Alexandre Pouille, Emmanuel Farge, and Lilianna Solnica-Krezel, The Journal of Cell Biology, Vol. 180, No. 1, 221-232. Here, the saddle point is quite visible, I have circled it in red (point-col, in french)

and in :

The ECM Moves during Primitive Streak Formation—Computation of ECM

Versus Cellular Motion Evan A. Zamir¤, Brenda J. Rongish, Charles

D. Little PLOS biology 2008

Therefore, this saddle point does exist. The usual picture of a development oriented in the antero-posterior direction is wrong. The recent dipolar description by Chuai, Weijer and co-workers is also wrong.

Description

of the flow with a

hydrodynamic dipole

(The Mechanisms Underlying Primitive

Streak Formation in the Chick Embryo Manli Chuai and Cornelis

J. Weijer, Curr Top Dev Biol

81: 135-56, 2007).

In fact, the embryos of tetrapods form from a quadrupolar movement, whose simplest

description in terms of flow is found in

(V. Fleury, Organogenesis, 2, 1, 6 2005) :

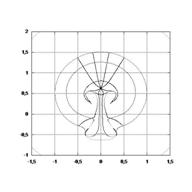

The image to the left shows the velocity pattern (stream lines), and the image to the right shows the progressive deformation

of the discoidal embryo.

This flow is obtained by supposing that the cells in Koller's sickle pull uniformly.

Koller's sickle, or Rauber's sickle is an area inherited from cortical rotation, which forms a sharp line, in the form of a crescent

where cell properties are singular. It is located in the caudal area of the embryo.

It is a remote consequence of the ovocyte a-p asymmetry, and it positions the first cell cleavage.

During the first cleavages of the cell, successive cellular cleavages propagate the initial asymmetry to create this sickle,

or crescent.

The intersection of the sickle, and of the AP axis is the presumptive navel. The AP axis being defined by the point of entry

of the spermatozoid.

The flow speed of a single cell is of the following form

with a prefactor

taking into account the viscosity and blastula thickness

v=curl(Y(x,y)), with Y (x,y)=x/x2+y2,

Dipolar field of the form v=curl(x/x2+y2),

created by a dipole of force concentrated at (0,0)

therefore

a quadru-pole is of the form (x-a)/(x-a)2+(y)2

–(x+a)/(x+a)2+(y)2.

a corresponds to the location of the center of the vortex, or the apex of the pulling segment. This is a

quadru-pole, which is singular at the saddle-point; it is obtained by assuming that

the pulling segment is

quite thin. One can relax this assumption by supposing that the pulling area is a bit wider.

In this situation one needs to integrate forces over a rectangle. One then finds a solution :

v=rot(Y (x,y), avex Y (x,y)= òr1r2 (x-a)/(x-a)2+(y-b)2 da-

òr3r4 (x-a)/(x-a)2+(y-b)2da

~Ln(r1)-Ln(r2)-(Ln(r3)-Ln(r4)), where r1, r2, r3 et r4 are the distances

to the centre of the vortices corresponding to the edges of the pulling zone.

Technically this amounts to relaxing the divergence at

the singular point of the quadrupole.

The quadru-pole

will then be obtained as a limit when the centres M1 et M2 et M3 M4 of the vortices merge.

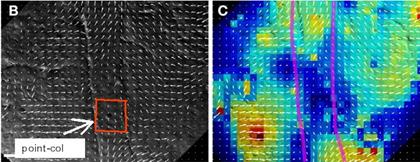

In a more pictorial fashion, the streamlines become

:

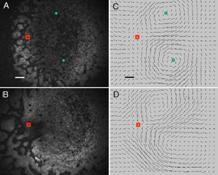

As explained in my article (V. Fleury, Revue des Questions

Scientifiques, 177, 3-4, 235 (2006)), and in the supplementary material of V. Fleury, A. Al-Kilani,

M. Unbekandt and T.-H. Nguyen, Organogenesis, 3,

1, 49 (2007). To the right, an image obtained in Cornelis Weijer lab in Dundee, the red square, which is found in the original publications, shows the

saddle-point (explicitely described as such in the original article, C. Cui, X. Yang, M. Chuai, J. A. Glazier, C. J. Weijer, Dev. Biol. 284, 37 (2005))

As we see on the figure, and as explained in the papers, it is not necessary to have a complete vortex inside the blastula. The flows may virtually exit the blastula. The blastula itself is a moving, free boundary. Please see the animations page for animated images of blastulas. (It appears that Jacobson and Gordon actually performed animations of the same sort in... 1976: A. G. Jacobson and R. Gordon, The Journal of experimental zoology, 197, 2 (1976), these simulations are stupefying). In addition, the Stokes-Whitehead paradox implies that the flow is faulty in the core of the vortex, where the speed diverges. Actually, inside such a singularity, the core revolves as a solid revolving object. (One needs to re-inject the advective term v.grad(v) into the Stokes equation to treat the singularity).

Moreover, if we suppose that all cells start to pull (and not just Koller's sickle), one obtains a solution of solid revolving vortices

(like a merry-go-round) which is a classical hydrodynamic solution.

(See Clarifying tetrapod embryogenesis , a physicist’s point of view,

Vincent Fleury, EPJ Applied Physics).

With such a model, one understands quite well the formation of tetrapods

.

First of all, let us insist that so far, I dealt only with stationary flows. Still,

hydrodynalmics teaches you that such vortices cannot be stationnary.

(See for example the course by Paterson, First course

in Hydrodynamics, Cambridge University

Press, 1988). This explains why the experiments on these vortices are so difficult, and they all see

moe or less well formed vortices, not always identical. This is because there exists a non-steady state,

the vortices actually drift, just as smoke rings move; that is not an analogy, it is the very same thing (although viscous).

The only difference is that smoke rings are not constantly dragged : once they are emitted by the mouth they slow down,

because of diffusion. While the vortices of the blastulas are constantly pulled forward by the cells.

-see for exemple : The decay of a viscous vortex pair, Brian Cantwell

and Nicholas Rott, Physics

of Fluids, 31, 11, November

1988).

This movement of the vortices which are translated in their own flow is taken into account

in V. Fleury, Revue des Questions Scientifiques, 177, 3-4, 235 (2006),

This is done by simply advecting ("transporting") the centre of the vortices, in the flow created by all the others except the one which is moved.

This is a classical emergent properties of dynamics of singularities. A simple calculation gives :

Therefore, the winding brings the tissue closer to the body axis, and makes it lift up by a mechanical effect (the winding

creates a stress gradient oriented towards the center of the vortices, growth occurs

by buckling in the direction of decreasing stress).

One interesting point is that this model explains very simply why some animals

have legs, and others not (apeds). The winding localizes the gradients, which may, or may not, extend a limb. It is clear that, if there is

no winding at all, the animal will just have a tail. As the winding gets stronger, the animal is more likely to have limbs, in proportion

of the strength of the vortices.

The gradient of stress is localized towards the engulfments, and it is of course not necessary that en entire vortex be observed.

What matters is the progressive engulfment of the tissue towards the median axis.

(Please pay no attention to ridiculous and defammatory internet pages or comments dedicated to scorn my work, especially, Dr PZ Myers on his blog makes

a hypnotic attempt to debunk these facts, although it is now well admitted among experts, even in the comments of his own blog, that embryogenesis in tetrapods

occurs via swirling of vortices).

Animals then have "latent" limbs, just as we have a "latent tail".

Now, the winding may also lead to disappearance of limbs, as in snakes, when the flatenning and the stretch along the median axis

is too strong.

It is worth underlining one point:

The winding, of course, is not arrested at the stage where such

lines are seen:

From X. Yang, D. Dormann, A. E. Münsterberg, and C. J. Weijer, Developmental

Cell, 3, 425 (2002). The red square represents the saddle-pointfAntero

in the recent published work.

The movement continues, since the very formation of an animal is a matter of a continuous flattenig and stretching

("convergent extension", as stated in biology).

It is a single flow,unique.

In order to understand the entire process, one needs to follow the entire "movie", even later

on, as the movie that can be found in the supplementary material of one of our papers, with Ferdinand Le Noble.

(F. LeNoble, D. Moyon, L. Pardanaud, L. Yuan, V. Djonov, R.

Mattheijssen, C. Bréant, V. Fleury and A. Eichmann, Development, 131, 361 (2004).

see supplementary material).

Progressively, the animal elongates along the Antero-posterior axis, while the lateral plates bump outwards

get closer to the body, and become a small bud-paddle like. "Staging" of the embryo growth gives a completely wrong view of what is going on.

.

Scheme of the outgrowth of hindlimbs.

Scheme for the entire embryo. To the right : a calculation closer to the true flows, obtained by positioning a bit better the initial vortices (which amounts to considering a curved sickle and not a straight segment as the source of flow).

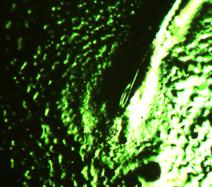

The winding which is associated to limb formation is very conspicuous

on many stainings of lateral plates, such as the one below of Tbx4, or the shadowgraph image showing the winding which you may see at the shadowgraph page of this site

See also the last article of Kees Weijer, where it seems to me the winding is also quite visible (I should check)

Finally, one must say that at the saddle point itself, the stream function may be simplified as

Y(x,y)= kxy, so that the flow is v(x,y)=(-kx,ky) (development of 4 vortices around the stagnation point).

This shows that the flow is purely elongational at the stagnation point,

This means that it flattens in one direction and extends in the other affinely(hence the phrase

« convergent-extension »).

Image of the transport in a hyperbolic flow. The streamlines are hyperbolas, and the flow is

elongational : it merely stretches the shape in one direction, and flattens it in the other,

(« streakline »,

not to be confused with « streamline »),

although streaklines and streamlines are identical in steady state.

This view is what is called a lagrangian view as opposed to an eulerian picture.

One consequence of this pattern of flow, is that molecular stainings follow

passively the transport in the flow, as observed. Therefore : all molecular stainings have a "dynamic"

evolution, as often stated in biology.

Images of stretching of patterns of expression in the

hyperbolic flow (from T. Mikawa, A. Poh,

K. Kelly, Y. Ishii, and D. Reese,

Developmental dynamics,

229, 422

(2004),

et D. L. Chapman, N. Garvey, S. Hancock, M. Alexiou,

S. I. Agulnik, J. Thomas, R. J. Bollag,

L. M. Silver, and V. E. Papaioannou,. Dev. Dyn. 206, 379 (1996).

Therefore the flow transforms the source of flow (Koller-Rauber sickle) self-consistently with the flow itself, in the vortices, which are transported by

the proper flow which they impart on each other. This closes mathematically the problem. .

Voilà. If you managed to follow all the details up to here, you may

have a flavour of the origin of tetrapods : they are not the consequence of some contingent chance,

but the hyperbolic attractor of a self-consistent flow, which, taking into account the initial cross pattern

of the first two cleavages scales up the pattern into an elongated, bilateral animal, with four limbs.

It is very simple, actually. My feeling is that we humans have made a lot of fuss with something exquisitely simple.