A few words about the growth of organs ("branching morphogenesis")

|

A few words about the growth of organs ("branching morphogenesis") |

|||

| I am interested in the growth and morphogenesis of the so called branched organs, this includes : the kidney, the lungs, several glands, lacrymal glands, salivary glands, prostate, mammary glands etc. I have suggested an analogy between the pattern of viscous fingers in physics, and the "fingering" of an epithelium against a mesenchyme which supposedly generates the branched pattern of these organs. This analogy gives a straightforward explanation to the development of organs. When a fluid A is pushed against and through a more viscous fluid B, the interface between the two is unstable and branches. If you want to do a viscous fingering experiment, please take two covers of CD boxes, flatten a drop of oil or of any viscous material, and then pull apart the two CD boxes. The plate to the right shows the development of a GFP transgenic kidney (Lab Frank Constantini, U of Columbia NY, coll. with Tomoko Watanabe). |  |

||

| In this system, physics plays a great role. The pressure inside, the tension forces, and any sort of obstacle like other branches or the surrounding capsule, or any other orghan around which may modify boundary conditions. One should realize that there always exists a fluid, inside the bracnhes (inside the "lumen"), and that this fluid is continuously produced by the epithelial surface, thereby generating an internal pressure. This pressure pusshes the organ forward during development (hence for example the painful breast of pregnant women). The photo to the right shows the collision between two branches during kidney development, which induces a tip-splitting of both branches of the collision. |  |

||

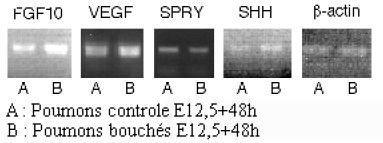

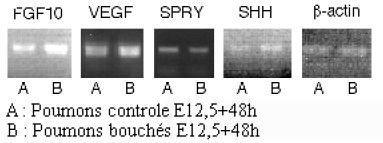

| During the PhD work of Mathieu Unbekandt (in coll. with David Warburton's lab in Los Angeles), we have shown that, in effect, several important genes related to the growth were mechanosensitive. This can be proven by amplifying the RNAs of these gens (by PCR). The photo shows the PCR of 4 genes, a control lung, an "inflated" lung (more pressure inside), the beta-actin serving for comparison. |  |

||

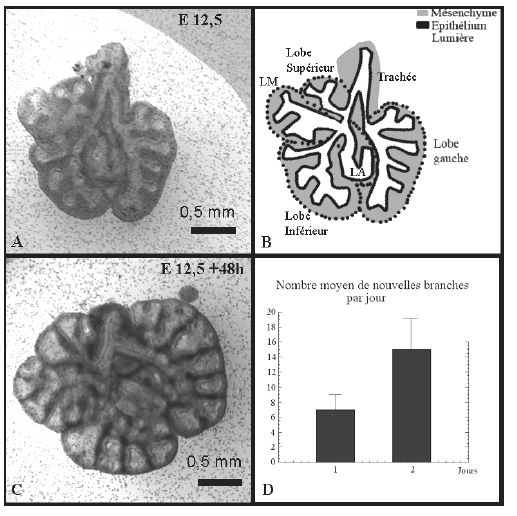

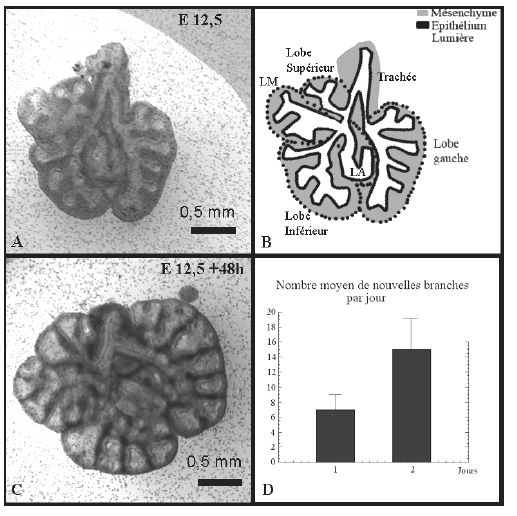

| Direct morphogenetic effects are quite conspicuous. The number of branches grows much faster in a clamped (occluded) lung, from which the fluid cannot escape (hence a higher pressure). The photo shows a control lung, and a clamped lung, the number of branches increases twice as fast in the clamped lung. (murine lings, cultured in vitro at stage 12.5, and onwards). |  |

||

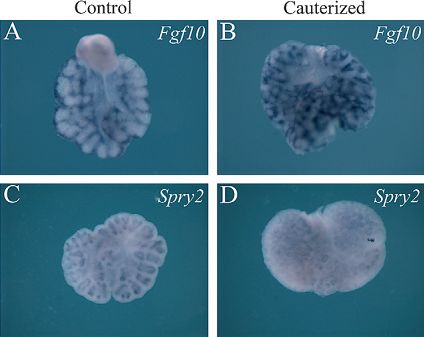

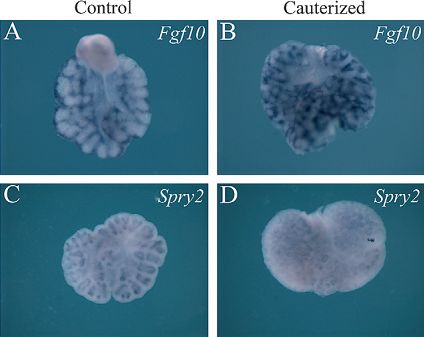

| In reality, one may even argue that, when we look at a staining map (for example of FGF10) we actually see something like a stress map. Of course, the colors are not linearly related to the stress, but nevertheless, it is some sort of a stress map. Such images are often provided in physics when doing what is called polaroscopy (imaging of stresses by polarizing techniques). (Coll. with the children's Hospital, USC, David Warburton's lab, Image obtained by P. Del Moral et M. Unbekandt) |  |

||

| By integrating the mechanotransduction into a model of growth, one can form a closed model of development. In this view, scalar quantities like concentration of growth factors, are slaved to stress fields, and a closed mathematical formalism can be derived. The true morphogenetic field is the deformation field. See Mathieu's thesis Thesis manuscript of Mathieu Unbekandt. |  |

||

| The quotation of this page : | "If there is nothing after death, who cares, if there is something, what an adventure" François Miterrand | ||